By Richard Campbell

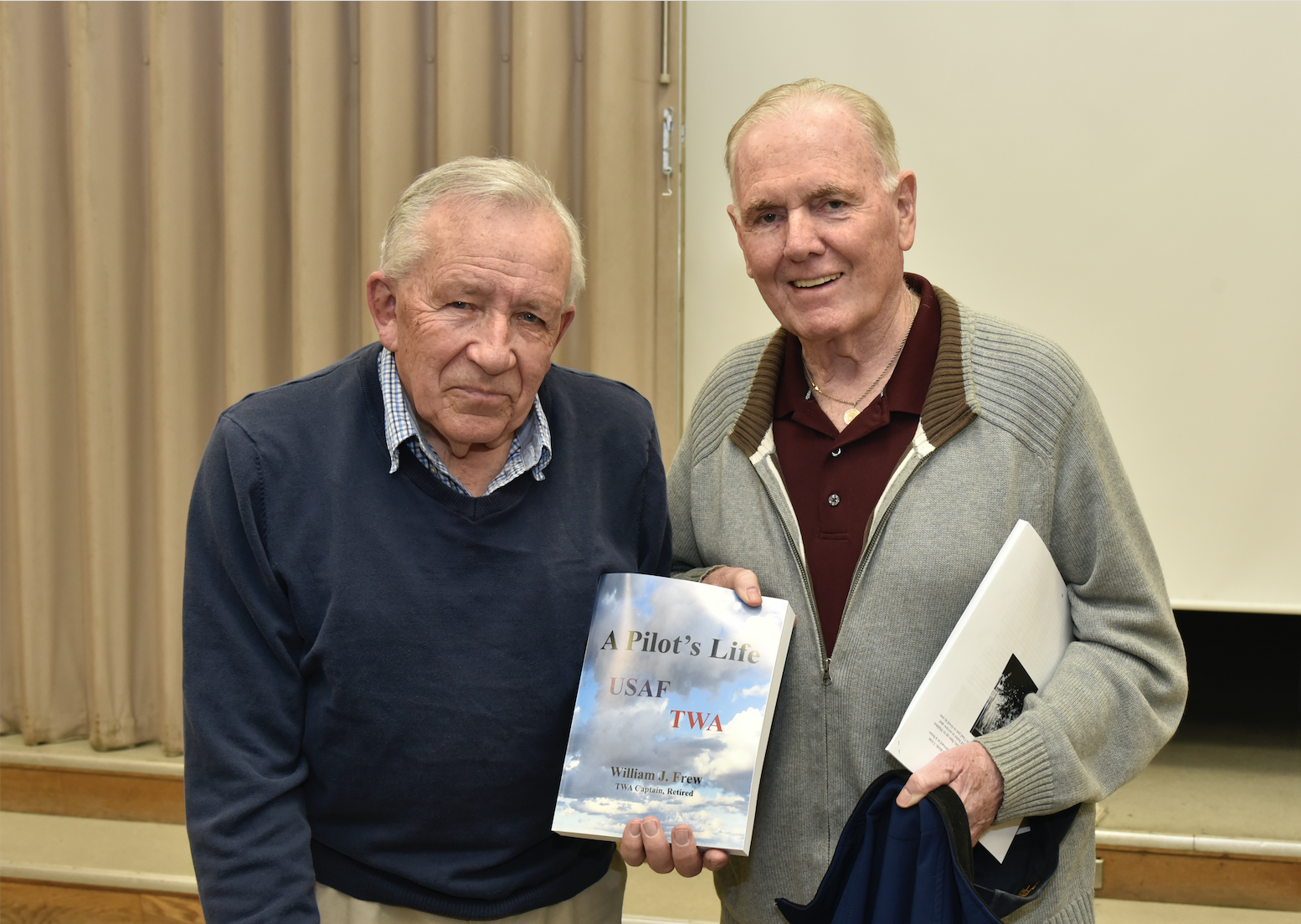

This past Monday night at the South Boston Branch of the Boston Public Library, retired pilot and author William Frew gave a brief talk on his book: “A Pilot’s Life”. There was more than the usual crowd that attends lectures presented by the South Boston Historical Society in the small program room, and the topical treatment of Bill Frew’s experiences moved by quickly. He started his presentation with some first-rate jokes about General MacArthur, and then moved on to anecdotes from his training, and aviation history.

The stories he told were primarily about his life in training to become a pilot, as well as navigating the personal logistics of handling operations on a series of basses throughout training in the US Airforce. Growing up in South Boston as a boy Frew described being captivated by the planes that flew in around Boston during World War II. Coming from a family with a military background, (his father was in the Merchant Marines and his uncle was an assistant to General MacArthur), it seemed natural for him to enter into training and service in the US Air Force.

Of course, flying jet fighters is anything but a natural act to do, so when former Captain Frew described some of the comical mishaps and close calls; the audience alternately chuckled and gasped with amazement. Frew was in the Airforce during the post-World War II, Cold War period, and flew commercially during the halcyon days of American aviation. His description of North American T28, and the modified Beechcraft T34 American trainer aircrafts in motion was enveloped with a sense of personal memory, and a kind of low key gallows humor.

Keep in mind, these are small planes by today’s standards, but they had up to a 40 feet wing span and can fly over 300 MPH and up to 35,000 feet. Even though the engines were quite reliable, unlike larger craft, there wasn’t a lot of protection if you crashed. In describing some of the fatal accidents other pilots had, Frew made it clear that in training, that pilots worried about being cut from the force, and could wake up with nightmares of going down. Since he was training in a non-war period, he had time to do things like coach little league baseball, and get to know the locals near the base.

He furthered his training on a T33 Jet fighter, a plane with a 455 MPH cruise speed, that could go up to 45,000 feet. After navigation and flight training he also flew KC135 tankers that were used to refuel B52 planes in mid-air. These would have been modified Boeing 707 planes, much like modern day jet liners, and very good for training to become a commercial pilot. The process of refueling requires a kind of precision in flight and attention to safety. The plane that Frew eventually piloted for TWA, the Constellation, had a storied history. It was designed by Lockheed at the request of Howard Hughes, who had purchased a majority share of the company in 1939, and models were quickly adapted by the military as C69’s after breaking the transcontinental speed record in 1944. When the war ended TWA bought them all back from the military and refitted them for commercial use. The plane really heralded the beginning of luxury air travel in the United States.

The irony is that even after flying some of these birds, early on he had to get someone from the Air Force crew to teach him how to drive his first car. The stories he told of being treated royally by farmers in the mid-west, and some of the harrowing reminders of racism in the South, reminded the audience of what a different time it was then. The Cold War was different from our current troubles, and the urgency regarding nuclear annihilation seemed stronger. He mentioned that he was lucky in getting good trainers, both patient and knowledgeable- when sometimes he said the trainers could be mean. He spoke with fondness about training with the legendary Dutch Holland and being stationed near SAC Headquarters in preparation for war activity.

By the time he got to civilian life and flying for TWA, our time was up. I only wished that young would-be pilots thinking of attending the Air Force Academy could have been in attendance, but the history buffs enjoyed the talk immensely. William Frew’s book: “A Pilot’s Life” was added to the Library of Congress Collection, an honor not normally bestowed upon books that are not published by major publishing houses. To purchase the book, go to Harvard Book store, or online at: http://www.harvard.com/book/a_pilots_life/